History

Early Estonian History

Estonians are among the world’s oldest peoples, having continuously inhabited their land for thousands of years. Experts estimate that Estonians have lived on their land for between 5,000 and 8,000 years. From approximately 6,000 B.C. until 1208 A.D., Estonians were independent, successfully fending off attacks from outsiders while building wealth. Their long coastline was a defensive advantage.

In 1201, German merchants and missionaries established a trading post in Riga, south of Estonia, in the land of the ethnically kindred Livonians. They noted the region’s wealth and saw vast opportunities. With the blessing of Pope Innocent III, the German bishop Albert assembled a mercenary army to conquer the region. “The Baltic Crusade” was launched on the pretext of bringing Christianity to the heathens.

Attacks on Estonia began in 1208, a time when Estonia’s population was around 175,000. The invasion lasted nineteen years, with Estonia assaulted by German mercenaries from the south, Danes from the north, Swedes from the west, and Slavs from the east. Primarily farmers and fishermen who assembled militias only when needed, the Estonians were no match for four professional armies with superior weaponry. “Baltic Germans”, the descendants of these original occupiers, controlled the land for centuries, even though Estonian rule passed from Germans and Danes to Swedes and Poles, and finally to the Russians in 1721. Throughout these occupations, the Baltic Germans formed the local ruling bureaucracy, while native Estonians essentially remained serfs.

By the 1860s, Estonia’s “Great Awakening” had begun. This period marked a time of increased interest in Estonia’s language, literature, art, and music. During this decade, the national epic “Kalevipoeg” was published, and the poet and playwright Lydia Koidula penned numerous works honoring Estonia. The first song festival (Laulupidu) was held in 1869. “The Great Awakening” expressed an increasing desire among Estonians for national self-determination. That desire built until Estonia declared independence in 1918.

War For Independence

On March 15, 1917, Czar Nikolai II abdicated the Russian throne amid the chaos created by Russia’s involvement in World War I and socialist revolutionary action at home. On October 23 of that year, twelve socialist revolutionaries calling themselves Bolsheviks met in Petrograd and decided forcibly to overthrow Russia’s Provisional Government. They succeeded on November 8, 1917. Vladimir Lenin emerged as “Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars.”

An Estonian Diet (Maapäev) had been formed in Czar Nikolai’s absence. Seeing an opportunity in the Bolshevik takeover of Russia, the Diet declared sovereignty over Estonia on November 28, 1917. The Bolsheviks quickly dissolved the Maapäev and drove pro-independence Estonians underground. But a few months later, as the Bolsheviks retreated from the advancing German army, the underground Maapäev seized the opportunity on February 24, 1918 formally to declare Estonia’s independence.

German troops entered Tallinn the next day, and by March 4, 1918 the German army occupied all of Estonia. However, Germany’s defeat at the end of the World War I forced the German army to vacate Estonia by November 1918. The Russian Bolsheviks invaded again on November 28, 1918. A newly formed Estonian army fought back in a bloody conflict. For a short while, the Estonian army had to fight a war of independence on two fronts. The Baltic Germans, who did not want to give up their power in Estonia, recruited a mercenary army to fight for their interests. They attacked from the south on June 5, 1919, but were soundly defeated at a major battle in Võnnu on June 23, 1919.

Estonia eventually defeated the Russian army. On February 2, 1920, the Treaty of Tartu was signed between Estonia and Soviet Russia. The treaty recognized Estonia’s independence and sovereignty and Russia renounced in perpetuity all rights to the territory of Estonia. Estonians won their independence at a heavy toll. Estonia suffered nearly twice the number of casualties that the United States did during its revolution—even though Estonia’s population was about a one-fourth that of the colonies in 1776.

First Independence

After establishing independence, Estonia was admitted to the League of Nations in 1921. Having been occupied by Czarist Russia for nearly two centuries, Estonia was initially poor compared to other Western nations, but the country quickly adapted. Estonia’s first constitution was roughly based on Switzerland’s. A six-day, forty-eight-hour work week became the norm. Unemployment never rose above 2% (1% being the average) during these years, and Estonia’s literacy rates ranked among the highest in the world, as they still do. Estonia exported goods around the world. Free speech and religious liberty were guaranteed by law.

Political stability was occasionally challenged by the Soviet Union. In 1924, a Moscow-instigated team of Communist “revolutionaries” attacked various government installations. Estonian government troops repelled the attacks in one day.

Estonia modernized quickly, emerging from two hundred years of Czarist rule to become a Western European–style democracy. By 1938, the Baltic countries were importing goods valued at $293 million, with the value of exports being $292 million. In the same year, Soviet Russia’s imports totaled $261 million and exports totaled $250 million.

In just twenty years, Estonia had worked economic and political miracles. Its economy was roughly equivalent to that of its northern neighbor, Finland. In 1939, growth and prosperity seemed right around the corner for Estonia.

Soviet Occupation

On August 23, 1939, Adolf Hitler and Josef Stalin signed a treaty called the “Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact” (MRP). The MRP made Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union allies, and divided Europe between the two empires. One week later, on September 1, 1939, Hitler invaded Poland from the west; shortly thereafter, Stalin invaded Poland from the east. These invasions marked the start of World War II.

On September 24, 1939, Stalin issued an ultimatum, threatening to invade and occupy Estonia if it did not permit him to maintain military bases there. The carrot he offered was a promise to honor Estonia’s sovereignty. He issued similar ultimatums to Latvia and Lithuania. Having seen the fate of Poland, the three Baltic countries saw no alternative but to yield. In June of 1940, the Soviets broke their promises, took over the Estonian government, and killed or deported virtually all the country’s political and business leaders. The same thing happened in Latvia and Lithuania. Stalin subsequently declared that the Baltic countries had “volunteered” to become part of the Soviet Union.

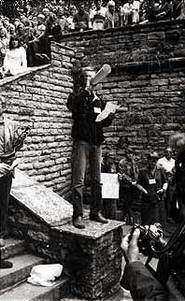

The Singing Revolution

Most people don’t think about singing when thinking about revolutions. But in Estonia song was the weapon of choice when, between 1987 and 1991, Estonians wanted to end decades of Soviet occupation.

The Singing Revolution is the name given to the step-by-step process that led to the reestablishment of Estonian independence in 1991. This was a non-violent revolution that overthrew a very violent occupation. It was called the Singing Revolution because of the role singing played in the protests of the mid-1980s. But singing had always been a major unifying force for Estonians while they endured fifty years of Soviet rule.

In 1947, during the first song festival (Laulupidu) held after the Soviet occupation, Gustav Ernesaks wrote a tune set to the lyrics of a century-old national poem written by Lydia Koidula, “Mu isamaa on minu arm” (“Land of My Fathers, Land That I Love”). This song miraculously slipped by the Soviet censors, and for fifty years it was a musical statement of every Estonian’s desire for freedom.

The song was not allowed on the song festival program in the 1950s. But then, in the early 1960s, Estonians started defiantly singing the song against Soviet wishes, and by 1965 it was included in the program. At the hundredth anniversary of the song festival in 1969, the choirs on stage and the audience as well started singing “Mu isamaa on minu arm” a second time in the face of stern Soviet orders to leave the stage. No one did. The Soviets ordered a military band to play and drown out the singers.

But a hundred instruments is no match for over a hundred thousand singers. The song was sung repeatedly in the face of authorities. There was nothing the Soviets could do but invite the composer on stage to conduct the choir for yet another encore and pretend they intended to allow this all along. When Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985, Estonians began testing his policies of perestroika (economic restructuring) and glasnost (free speech) to see how far they could go. The first test was in 1986, when Estonians protested a plan to build phosphorite mines throughout the country.

The environmental issue provided a relatively safe means of seeing whether people could truly speak openly without Soviet permission. Protestors did not suffer significant repercussions, and the mining project was eventually stopped. The first test was a success. A short while later, a more radical demonstration in Tallinn’s Hirve Park openly spoke of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (the secret agreement between Hitler and Stalin that led to the Soviet invasion of Estonia in 1939–40). The KGB observed this event, names were taken, leaders were harassed, but, much to the demonstrators’ surprise, no one was arrested.

It was illegal to own an Estonian flag during these years. Estonians tested this law by flying three separate blue, black, and white banners that effectively became the flag when flown side by side.

In the mid-1980s, six new rock songs became rallying cries for independence. These songs were repeatedly sung in large public gatherings. Soviet authorities wanted to ban them, but weren’t sure what to do in light of glasnost.

Momentum and courage grew. The Estonians calculated that as long as they shed no blood, Gorbachev wouldn’t be able to send in tanks to quash demonstrations. Such blatant censorship would be an international embarrassment to his carefully cultivated image. So people pushed Moscow as far as they could, taking great care to stay non-violent.

In this sense, the Singing Revolution was a strategically non-violent movement.

But there were several different political approaches to gaining independence. These largely fell into three organized groups: The Popular Front, The Estonian National Independence Party, and The Heritage Society. Each group had a different philosophy about how to gain freedom…even how to define freedom.

Many Estonians supported more than one of these organizations; some supported all three. Others felt more loyal to one or the other. There was significant tension among some of the leaders. Those who moved more cautiously felt that the “radicals” would bring Soviet retribution on Estonia, as had happened in Hungary in 1956 and in Czechoslovakia in 1968; the “radicals” felt that working within the Communist system betrayed their country and dishonored those who had died and suffered under Soviet rule.

Matters came to a head in 1991 when Moscow hard-liners staged a coup d’état and placed Gorbachev under house arrest. As troops rolled into Estonia to quell any independence-minded thinking, Estonians decided to escalate their bid for freedom. Unarmed people faced down soldiers and tanks, while political leaders assembled to declare Estonia’s independence.

Acknowledgment: The history presented here draws from Ago Koerv’s “An Introduction to Estonia”.